Imagine someone whispering a thought so compelling that it burrows into your mind, unpacks its bags, and begins rearranging the furniture. That isn’t science fiction. It’s a psychological phenomenon made more potent by the mechanics of social media, the vulnerabilities of human cognition, and the viral properties of culture itself. When Leonardo DiCaprio’s character in Inception describes an idea as "the most resilient parasite," he might as well have been forecasting the age of algorithmic influence.

Elon Musk, never one to understate, calls them “mind viruses.” And while the term may carry the whiff of Silicon Valley melodrama, it has serious intellectual pedigree. Decades ago, Richard Dawkins introduced the concept of memes—not the internet jokes we share today, but cultural replicators: beliefs, phrases, and rituals that leap from one mind to another, using us as their hosts.

The anatomy of a viral idea

These aren’t just passing trends. They're ideas that take root, not because they’re grounded in truth, but because they’re easy to remember and hard to shake. In a digital world built for sharing, the qualities that help ideas survive have less to do with accuracy and more to do with emotional appeal. A claim that’s bold, shocking, or neatly confirms what we already feel is far more likely to spread than one that’s cautious or complex. Virality doesn’t reward nuance. It rewards reaction.

Fear spreads faster than facts

During the pandemic, misinformation about vaccines spread faster than the virus itself. On one side, alarmist claims about side effects ignited fears of tyranny and bodily violation. On the other, a sanctimonious dismissal of all scepticism framed any dissent as dangerous idiocy. What we saw wasn’t just a clash of opinions — it was a contagion of instincts. Fear and virtue-signalling spread faster than facts, locking people into teams. Rather than examine the arguments, many simply doubled down, swept along by the emotional charge of the moment.

This isn’t new — just faster

The mechanics behind this aren’t new. The witch hunts of early modern Europe were an early example of viral belief. A rumour in one town, a trial in another, and soon hysteria spread across regions—fanned by theology, ignorance, and the thrill of righteous punishment. Reason had little to do with it. Contagion did. Much the same could be said of revolutionary ideologies that swept across nations. Marxism, nationalism, religious extremism—these weren’t just sets of ideas, they were systems that reproduced themselves through repetition, ritual, and group identity.

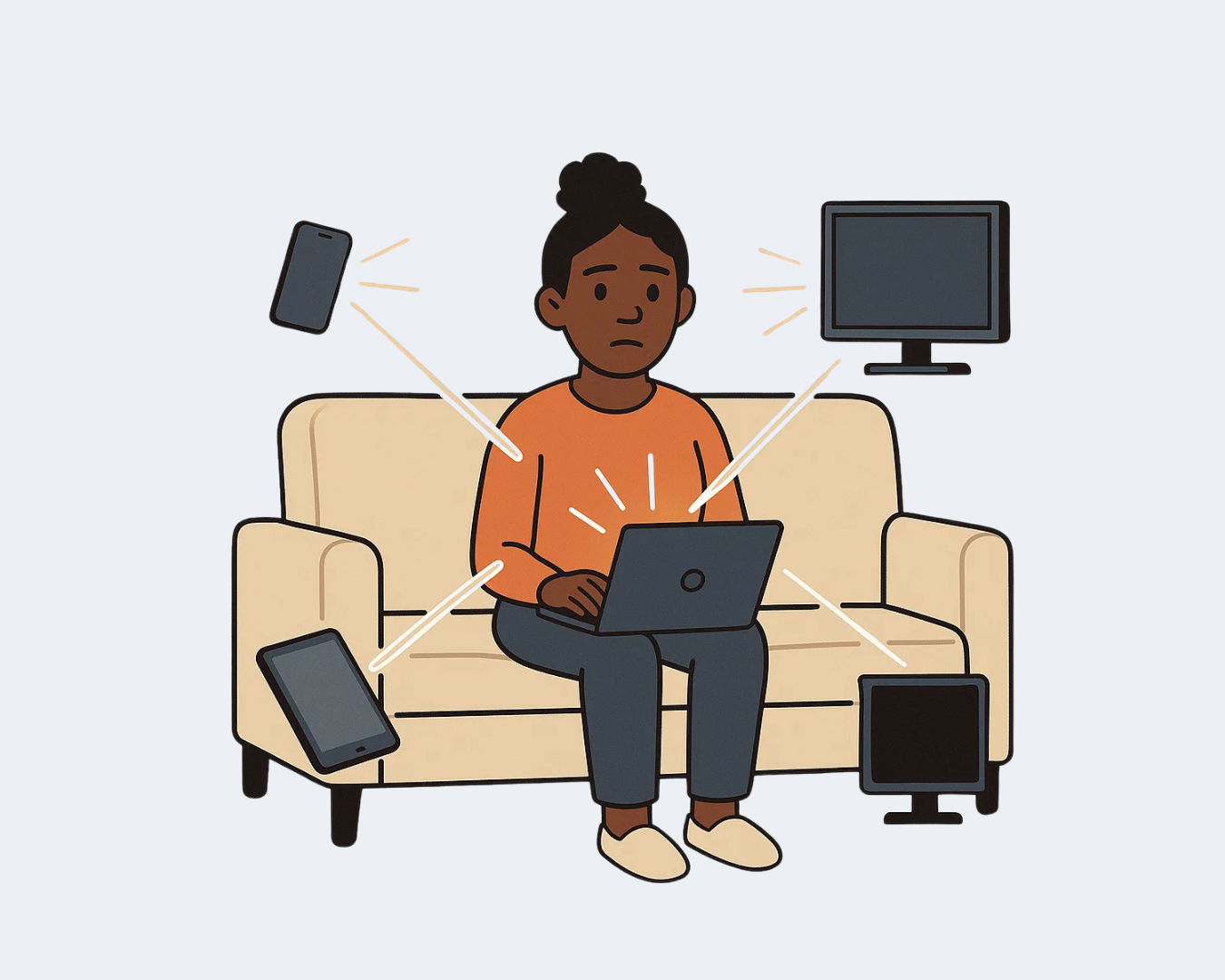

What’s changed isn’t the virus, but the velocity. In the era of Orson Welles' War of the Worlds, panic had a buffer. Today, a half-baked conspiracy can reach millions before breakfast, pushed by algorithms designed to maximise engagement, not accuracy. And the most dangerous ideas aren’t necessarily false—they’re emotionally true. They feel right, and our minds, built for survival not precision, often struggle to tell the difference.

When belief becomes identity

Emotions are fast, and often useful. They help us avoid danger and form bonds. But they also bypass reason. Viral ideas exploit that shortcut. They reward outrage with affirmation, identity with status, and belonging with protection. That’s what makes them powerful—and difficult to dislodge. They don’t just lodge in our thinking. They rewire the social logic around us. Once an idea confers group membership, disagreeing with it feels like exile. And the most successful memes are the ones that defend themselves, often by framing all criticism as betrayal.

It starts with an idea that strikes a nerve — something that feels obvious, overdue, or morally urgent. As it spreads, it gets repeated so often that it begins to lose its specific meaning and take on symbolic weight. Take the phrase “fake news.” Once a legitimate critique of low-quality reporting, it quickly became a catch-all phrase — a way to discredit anything one didn’t like. Its influence didn’t come from clarity, but from ambiguity. It could mean whatever you needed it to mean.

That’s when a meme stops being language and becomes a lens.

Slowing down the spread

But this isn’t inevitable. Mind viruses depend on their environment. They thrive in conditions that reward speed, emotional certainty, and tribalism. And the best way to resist them isn’t to call for censorship or hand over judgement to technocrats. It’s to strengthen our immune system—individually and collectively.

That means cultivating doubt where reflex would have us shout. It means learning to pause before sharing, checking our urge to react, and noticing when something feels too perfectly aligned with what we already believe. Viral ideas often come cloaked in urgency. They flatten complexity, present themselves as obvious, and reward conformity. When that happens, the wiser response isn’t to join the chorus. It’s to step back.

This isn’t about being clever. It’s about being deliberate. Speed is the virus’s greatest asset. Thoughtfulness is its biggest obstacle.

Mind viruses have been with us for centuries. But the digital world gives them scale and reach like never before. If we want to remain mentally sovereign in a culture engineered to hijack our attention, we’ll need to stay alert—not to what’s trending, but to what’s tunnelling in. In the battle for our minds, clarity is not a luxury. It’s a defence.

Further reading

Virus of the Mind: The New Science of the Meme by Richard Brodie

This groundbreaking book explores how ideas behave like viruses, replicating and spreading through human culture. A foundational text for understanding memetics and the psychology of contagious ideas.

The Meme Machine by Susan Blackmore

Blackmore delves into the evolutionary power of memes, explaining how they shape human behaviour and cultural evolution. Essential for anyone curious about the intersection of biology, culture, and ideas.

The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins

This classic work introduced the concept of the "meme" as a unit of cultural transmission, laying the foundation for modern memetics. Dawkins’ insights into evolution remain highly relevant today.

Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business by Neil Postman

Postman critiques how media shapes public discourse, making it an essential read for understanding the environments in which mind viruses thrive.

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

Nobel laureate Kahneman explains the cognitive biases and shortcuts that make our minds susceptible to manipulation. A must-read for anyone interested in psychological defences against mind viruses.

The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains by Nicholas Carr

Carr examines how the internet reshapes how we think, making it an insightful resource for understanding the rapid spread of modern memes and ideas.

Enjoyed this? Go deeper with our free Thinking Toolkit

A 10-part course to help you think more clearly, spot bad arguments, and build habits for sharper reasoning.

While you’re here...